The income tax rules for an exercise of non-qualified stock options are relatively straightforward.

You generally do not owe taxes when you are granted non-qualified stock options. You don’t owe when your non-qualified stock options vest, either. This no-tax timeframe allows you to defer income tax while potentially creating considerable wealth if the value of your shares increases.

Exercising your non-qualified stock options is what creates a taxable event. But because you control when you exercise your options, you can manage your income tax by deciding when and how many shares to exercise. You also control how well you plan for that taxable event when you create it by exercising.

Two Taxes to Consider for your Non-Qualified Stock Options

The lifespan of your options includes the period beginning when your options are granted and ending when you sell the stock. During this time, you need to consider two different types of tax you may need to pay:

- Earned Income Tax: Earned income is taxed as ordinary income and is subject to Social Security and Medicare wage taxes.

- Capital Gains Tax: Capital gains are taxed as ordinary income (for short-term capital gains) or as long-term capital gains, depending on the holding period of the stock.

The amount of gain subject to earned income tax and the amount subject to capital gains depends on several factors. Some of these include the exercise price of the non-qualified stock option, the fair market value when you exercise, how many shares you exercise, and how long you have held the stock.

How You’re Taxed When You Exercise your Non-Qualified Stock Options

When you exercise your non-qualified stock options, the value of the bargain element will be treated as earned income that is reported on your tax return the same way as your regular earned income.

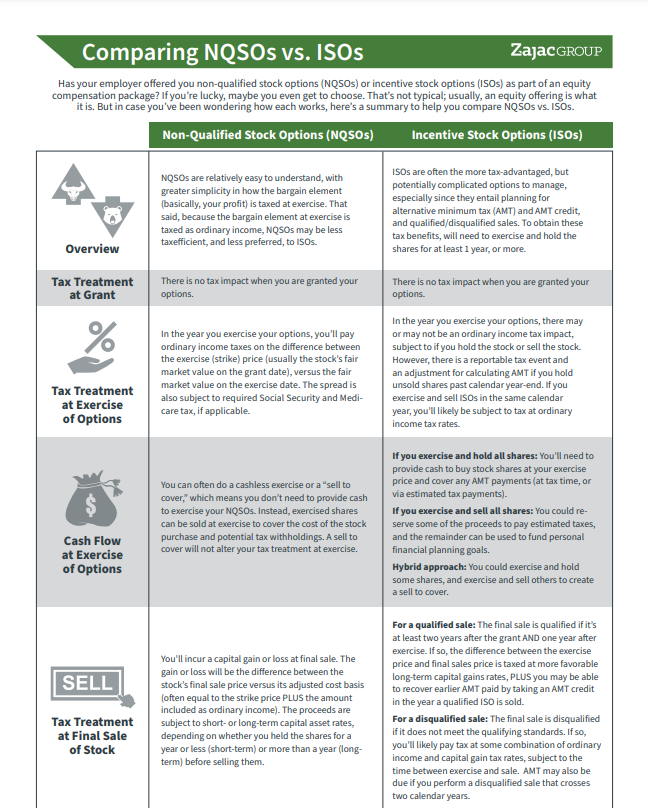

NQSOs vs. ISOs

This summary will break down the differences in how they work and what you should consider.

The bargain element is calculated as the difference between the grant price of the employee stock option and the exercise price of the stock option, multiplied by the number of shares. For example:

|

Number of Options |

Grant Price | Exercise Price | Bargain Element |

| 2,000 | $10.00/sh | $50.00/sh |

$80,000 |

If you exercise 2,000 non-qualified stock options with an exercise price of $10 per share when the value is $50.00 per share, you have a bargain element of $40 per share. $40 per share multiplied by 2,000 shares equals $80,000 of reportable compensation income for the year of the exercise.

The Cost Basis of Your Non-Qualified Stock Options

When you exercise your non-qualified stock options, you should pay attention to the price at which you exercised. This price will dictate the cost basis of the shares moving forward. The cost basis is necessary because it is used to calculate capital gain/loss upon a subsequent sale of the exercised stock.

The cost basis, generally speaking, is equal to the exercise price, multiplied by the number of shares exercised. In our example above, the cost basis is equal to 2,000 shares times $50/share, or $100,000.

Taxation Upon Final Sale of Non-Qualified Stock Options

When you exercise your non-qualified stock options, you go from having a right to shares of company stock to being an owner of company stock. As an owner of the stock, you can sell your shares immediately or hold them indefinitely. You may want to consider how concentrated equity fits into your financial plan before you make a move.

The period for which you retain ownership, and the value of the shares dictate how they will be taxed.

Stock shares acquired from an exercise and hold of non-qualified stock options are subject to capital asset tax rates. Short-term capital assets (assets that are held for less than one year) are taxed as ordinary income and long-term capital gains (assets that are held for one year or greater) are taxed at long-term capital gains rates. Generally speaking, long-term capital gains rates are lower and preferred over short-term capital gains rates.

Continuing our hypothetical example from above, we can explore what happens after you exercise and hold non-qualified stock options. First, we figure the cost basis to be $100,000. This is equal to the cost of the shares ($20,000) plus the amount claimed as compensation income ($80,000). We also assume tax rates for short-term capital gains are 33% and for long-term capital gains are 15% and the fair market value of the shares is $150,000. With these assumptions, we can calculate the after-tax values assuming the sale is short-term or long-term.

|

|

Cost Basis | Current Value |

Capital Gain |

Tax Due | After-Tax Value |

| Short-Term (33%) |

$100,000 |

$150,000 | $50,000 | ($16,500) |

$133,500 |

| Long-Term (15%) |

$100,000 | $150,000 | $50,000 | ($7,500) |

$142,500 |

In our example, the total tax paid on a short-term capital gain is $16,500. But long term capital gain taxes are only $7,500. Long-term capital gains offer a more favorable rate, considering it creates a tax bill that is over 50% lower.

(While this illustration indicates that long-term capital gains rates are better than short-term capital gains rates, it does not mean that you should always hold your stock for one year or more. Income tax is one of many factors that should impact your decision to keep or sell your shares).

Planning for Non-Qualified Stock Options

When you exercise your options, the spread between the grant price and the exercise price is taxed the same as compensation income subject to Medicare and Social Security tax. Any subsequent gain or loss from the date you exercise your options is taxed as a capital asset subject to capital asset rates.

The simplicity of income tax rules regarding non-qualified stock options does not mean there isn’t room for good non-qualified stock option planning. You will face a big decision when you exercise your options and need to pay the pending tax. The decision will be to do a cash exercise or a cashless exercise of your NSOs.

Advanced planning for non-qualified stock options may also mean exercising in calendar years when you are also exercising or selling incentive stock options as a means to increase or decrease the alternative minimum tax. Or you might exercise your options early, transitioning what may otherwise be compensation income into long-term capital gains (assuming a rising stock price).

Simple or complex, it’s important to know what the tax rules are for your stock options so you can begin your planning. Planning that should also consider when to exercise, how many to hold post exercise, and how this fits into your financial plan.

Daniel, this is an excellent article and clarifies so much for me. I do, however, have one question. The article states that “Upon exercise, the cost basis of the shares is set and is equal to the exercise price times the number of shares exercised. In our example above, the cost basis is equal to 2,000 shares times $50/share, or $80,000.” I get $100,000 when I do the math, not $80,000. Am I doing something wrong or misunderstanding? Please let me know. Thank you.

Yes, good catch. It has been updated!

Still says (7 paragraphs later)

“Continuing our example above, we have established a cost basis of $80,000 for the 2,000 shares of stock. ”

I assume should be a cost basis of $100,000.

Updated!

Daniel:

I believe that there are two issues that you should address, but haven’t. Those issues are:

1) Will the tax liability upon exercise of non qualified ESOs ever be deferred pursuant to IRC 83 c-3.

2) How does Section 16 (b) of the 1934 Act come into play, when executives have a choice to deliver shares or cash for the exercise price payment or taxes, when ESOs are exercised, and they decide to deliver shares.

Are my options pre tax purchased (401K) or after tax purchased?

Post tax dollars

With a NQSO exercise of a non-public company the company withholds taxes as ordinary income, based on the difference between the FMV 409(a) and the grant price. Is it true that once exercised, the FMV becomes the cost basis, and future transactions are treat as short or long term stock sales?

If the option exercise date is at the end of the month, and the company updates the FMV once the assessment is complete, is my tax withholding subject to change with the update for that one period? Does this change my stock cost basis, ie the value of the stock after exercise?

thanks

Do I pay withholding tax upon exercise of my NQ directly to IRS or my organization should pay it?

Hi – It might be both

Generally speaking, assuming you are an employee at a public company, statutory withholding (often 22%) will be w/held at exercise as part of a cashless transaction (or net settlement). Keep in mind this may or may not be enough to cover the total tax bill and an estimated payment to the IRS may be warranted.

If your company is private and no shares are sold at exercise to cover the tax, you may need to submit a check to your employer. I’d encourage you to check with your company to determine the details.

As a non employee outside director my options are non qualified. I believe the cost basis is adjusted to reflect the Price at the time of exercise since the amount reported on NE1099 will include the difference of the fair market value minus the stock option price as income for the tax year that the option was exercised.

Example $10.00 option price 1000 options Cost $10,000 to exercise

$50.00 market Value 1000 Shares Value $50,000 at exercise

$40,000 will be reported as income on the 1099-NE for the tax year when exercised. Income tax will be paid for that $40,000. The cost basis should be adjusted to reflect the $50.00 since tax has been paid. Otherwise the NON employee will pay twice once in the tax year of the exercise and again as capital gains at a future date.

Agreed – The cost basis would be the amount to buy the stock ($10) + the amount included as taxable income in the year of exercise ($40), for a total of $50 per share.

So… I exercised a set of NQO’s recently. I am now retired and living in a state with NO state tax. The option exercise took out medicare, social security and state tax… Why was this done? I received the grants while an employee, but sold them as a retiree in a different state.

Does this make sense? Is this right? if so, do we now need to file our taxes again back in our former state ???

Hi Art

Generally speaking, taxable income from the exercise of NQSO is going to be allocated to where you worked when some or all of the options were vested, not just where you lived when the options were exercised.

By way of simple example, lets assume that you lived and worked in one state for 3 out of 4 years of a vesting schedule, and moved to another no tax state for year 4. Lets also assume that you exercised all of the options at the end of year 4. In this simplified example, 75% of the income from exercise might still be taxable to the original state.

Multi state tax planning can be complicated, and it may make sense to consult a tax preparer if you are unsure.